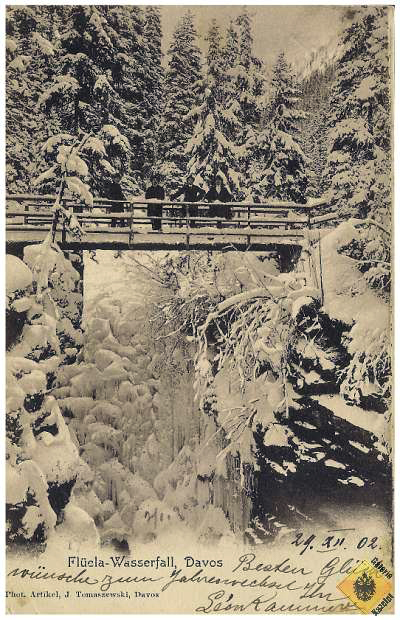

The Flüela Falls picnic is staged in May, a traditional month of spiritual renewal, but in this instance, Pieter Peeperkorn plans to announce his impending suicide.

Peppercorn has invited his closest friends at the tuberculosis sanitarium in Davos: Hans Castorp, Ludovico Settembrini, Leo Naphta, Clavdia Chauchat (Castrop’s and Peeperkorn’s lover), Leo Naphta, and Anton Ferge. He plans to picnic at the Flüela Falls, where he will serve pastries, hot tea, coffee, and two wine bottles and make his plans known.

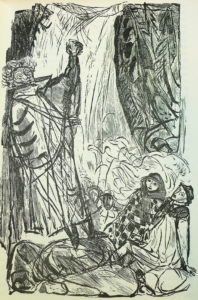

What Peeperkorn presumes is that his voice will rise above the rushing falls. Because he is a physically dominant personality, Peeperkorn cannot foresee being inaudible. The narrator explains, “Such words as they were accustomed to hearing from him, they could read on his lips or divine from his gestures: “Settled” and “Absolutely!” — but that was all. They saw his head sink sideways, the broken bitterness of the lips; they saw the man of sorrows in his guise. But then quite suddenly flashed the dimple, the sybaritic roguishness, the garment snatched up dance wise, the ritual impropriety of the heathen priest. He lifted his beaker, waved it half-circle before the assembled guests, and drank it out in three gulps so that it stood bottom upwards. The few words they understand are “settled” and “agreed.”

Peeperkorn’s oration at Fluela Falls. Felix Hoffman. In Thomas Mann. The Magic Mountain. New York: Heritage Press, 1962

Mann’s deeper meaning for the picnic is metaphorical. He contrasts the force of nature with the false belief that man is an indomitable force. A turn in the path revealed the bridge and the rocky ravine down which the torrent poured. At the” moment their eyes perceived it, their ears seemed saluted with the maximum of sound — for which infernal was the only right word. The volume of water fell perpendicularly in a single cascade, perhaps nine or ten feet high, and of considerable breadth, and foaming white shot away over the rocks. The frantic noise of its falling seemed to mingle all possible intensities and variations of sound — hissing, thundering, roaring, bawling, whispering, crashing, crackling, droning, chiming — truly, it was enough to drive one senseless.

Felix Hoffman’s illustration of the scene aptly positions Peeperkorn standing with his ist raised toward the falls above him.

Hans Werner Geissendorfer’s film ignores Mann’s intentions for his film adaptation of the episode. Geissendorfer rewrites the Flüela episode so that Peeperkorn (at best a heathen) kneels in a shallow stream at the top of the falls, speaking to God.

See Thomas. Mann. The Magic Mountain, Der Zauberberg, Edited by Translated by H. T. Lowe-Porter: Alfred A. Knopf, 1924. Reprint, 1934; Thomas Mann. The Magic Mountain. Translated by John E. Woods. New York: Vintage International, 1924. Reprint, 1996; Thomas Mann. Letters of Thomas Mann, 1889-1955. Translated by Richard Winston, Clara Winston. Los Angeles. University of California Press; Hans Werner Geissendorfer. The Magic Mountain (1982). The screenplay by Gillian Greenwood and David Thomas is based on Thomas Mann’s novel (1924); Ernest Ludwig Kirchner. Davos In Snow (1923), oil on canvas. Kunstmuseum Basel