Thérèse Raquin and her lover Laurent Le Claire murder her husband Camille at a picnic.

It’s a pivotal episode, proving Zola’s contention that people acting out the “fatalities of their flesh” become brutes humaines.

Everything about this picnic to Saint-Ouen is slightly off-kilter. Most importantly, Thérèse’s and Laurent’s apparent spirits are high, but their inner feelings are fraught with deep anxiety. The day promises to be the perfect day but turns unseasonably warm. There is no breeze. The grass is parched, and dead leaves crunch underfoot. The air smells unnaturally of fried fish and stale wine.

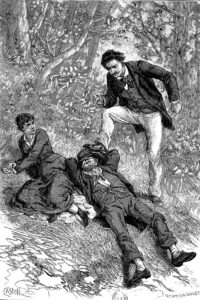

Waiting to dine at a table at a restaurant, anticipation of murdering Camille intensifies uncomfortably. In the heat, Camille becomes drowsy and falls asleep on the dead grass. This opportunity allows Laurent to mimic crushing Camille’s head. But without a signal from Thérèse, he resists. Instead, he cunningly improvises a plan to row out on the Seine and drown Camille, who cannot swim.

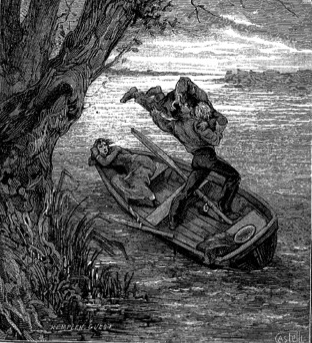

Horace Castelli after Kemplen Guest. Therese Raquin (1883)

The murder is astonishingly brutal. In the gathering darkness, Laurent steers to a place obscured by trees, and with mad ferocity, he grabs Camille tightly and throws him overboard. Thérèse remains impassive and then swoons. As Camille tries to climb back into the boat, Laurent leans over to push him away, but “Mad with rage and terror,” Camille bites a chunk of flesh from Laurent’s neck, causing him to release his grip. Still yelling, the current carries Camille away.

From that moment, Thérèse and Laurent’s relationship relentlessly declines. Their lust becomes loathing to the point they plan to murder each other. When that fails, they drink poison and collapse in a heap, her lips on his scar.

* Zola does not use pique-nique to characterize this outing because the French still defined it as an indoor meal. Zola got his idea for this sordid story from a newspaper story that did not involve a picnic.

Featured Image: Horace Castelli after Kemplen Guest. “Camille tumbled howling” [Camille tomba en poussant un hurlement] in Emile Zola. Therese Raquin (Paris: Paris: C. Marpon et E. Flammarion, 1883)

See Emile Zola. Thérèse Raquin. Translated by Edward Vizetelly. London: Vizetelly and Company, 1867; Emile Zola. Therese Raquin: A Drama in Four Acts. Paris, 1873. Zola first serialized the story as A Love Story in a literary magazine Artiste. Also, Simon Langton. Thérèse Raquin (1979). Screenplay by Philip Mackie based on Emile Zola’s novel; Therese Raquin (2001); (2001); Charlie Stratton. In Secret. Screenplay by Charlie Stratton (2014); Evan Cabnet. Therese Raquin (2015). Translated by Helen Edmundson and based on Emile Zola’s Therese Raquin: A Drama in Four Acts (1873)