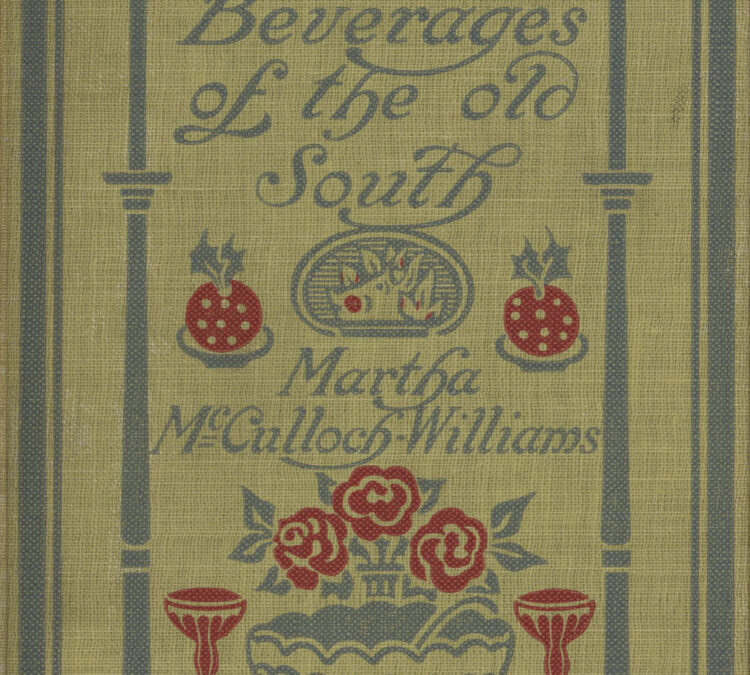

McCulloch-Williams’s memories of her Mammy’s cooking are the basis of Dishes and Beverages of the Old South. The pig barbecue is probably the same vintage of the Wilkes’s Twelve Oaks picnic garden as Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind. Her cookery is implicitly racist, slightly historical, and without proportions.

To make barbecues, McCulloch-Williams explains, “The animals, [must] butchered at sundown, and cooled of animal heat, after washing down well, are laid upon clean, split sticks of green wood over a trench two feet deep, and a little wider, and as long as need be, in which green wood has previously been burned to coals. There the meat stays twelve hours—from midnight to noon next day, usually. It is basted steadily with saltwater, applied with a clean mop, and turned over once only. Live coals are added as needed from the log fire kept burning a little way off. All this sounds simple, dead-easy. Try it—it is really an art. The plantation barbecuer was a person of consequence—moreover, few plantations could show a master of the art. Such a one could give himself lordly airs—the loan of him was an act of special friendship—profitable always to the personage lent. Then as now there were free barbecuers, mostly white—but somehow their handiwork lacked a little of perfection. For one thing, they never found out the exact secret of “dipney,” the sauce that savored the meat when it was crisply tender, brown all over, but free from the least scorching.”

See http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28491/28491-h/28491-h.htm; https://d.lib.msu.edu/content/biographies?author_name=McCulloch-Williams%2C+Martha%2C+approximately+1857-

* McCulloch-Williams was born in Clarksville, Tennessee, about 1857, but lived most of her life in New York City. She died in 1934.